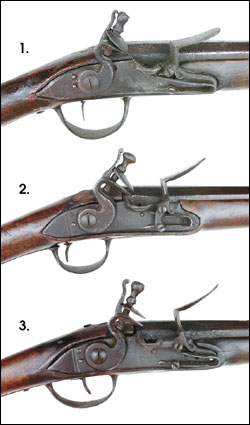

Charleville Trigger Guards  The early baluster Tulle musket pattern (1.) is circa 1697-1715. A popular, segmented, high-quality commercial hunting gun design with raised carving (2.) dates from 1720-1760. France’s double-pointed shape as used on Tulle’s marine hunting and military longarms (3.) is circa 1715-1755. The double-pointed military version was used on army issue Models 1717-1773 (4.), and a Model 1728 is shown. The Model 1774 (5.) shortened the forward end (the swivels moved underneath in 1754). The guard’s length was further reduced for this Model 1777 (6.). Its rear also became rounded, and two finger ridges appeared. |

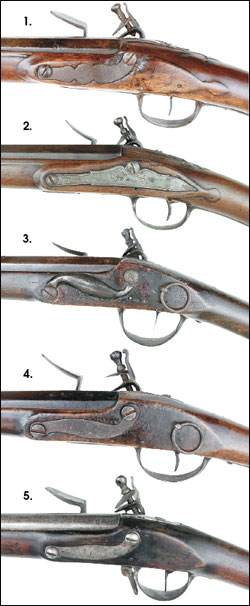

Charleville Locks  Tulle civilian and military locks (circa 1730-1755) had a flat/beveled edge plate, a lobed frizzen spring finial, a flat swansneck cock and a faceted flashpan, usually with an exterior bridle on the military patterns (1.). This example is marked, “A TVLLE,” below the pan (“V” became “U” in 1745). A distinctive vertical bridle joined the frizzen and frizzen spring screws on this Model 1717 (2.). The frizzen spring itself ended short of the forward lock screw tip, and its wide cock post faced a flat-backed upper jaw. The Model 1728 (3.) established a horizontal outside bridle and a rectangular cock post with a wrap-around oval top jaw. Its frizzen spring extended to cover the front lock screw tip. The new Model 1763 (4.) design installed a straighter 63⁄4" lockplate (shortened by 1/2" in 1766) that had a ring supported cock and added a horizontal hole to the slotted jaw screw. An American “U.S.” stamp appears on this tail (most are found without surcharges). The sling swivels have moved under the stock in 1754. Beginning in 1770, the lockplate, cock and flashpans became rounded and the cock’s post acquired a stubby upper end (5.). The Model 1774 (shown here) added a short, squared frizzen front stud. “Charleville” engraved under the pan establishes its source. The new Model 1777 (6.) introduced a sloping brass flashpan and bridle lacking a rear fence, plus a forward bend to the frizzen top. The shorter trigger guard also added two rear finger ridges. |

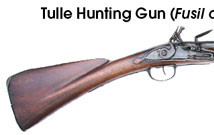

Charleville Sideplates The flat “L” sideplate with an oval center is found on most Tulle-made marine military and hunting guns (1.) circa 1720-1755. Observe the typical raised stock borders on this civilian fusil de chasse. An engraved triangular design was used with quality hunting arms (2.) circa 1730-1755. The early French rounded military “S” pattern and shoulder sling ring (held by a stud with a nut inside the stock’s lock cavity) are 1697-1715 (3.). The traditional flat “L” form began with the Model 1717; a Model 1728 (4.) is shown. Notice the absence of stock carving on France’s army muskets and continuation of the flat “L” shape in this lighter Model 1766-1777 series (5.). Its Model 1766 breech shows American 1777 New Hampshire markings. |

|

Used in large numbers by American Colonists and French troops fighting against the British, the “Charleville” muskets are the French arms that saved the American Revolution. The 18th century was a

period of incredible change that reshaped the political map of

Europe and the Western world—and that Group I: The Compagnies

Franches de la Marine While the British

settlers created farms and towns in the European tradition

(including a preference for heavy muskets and fowlers), settlers in

New France focused on exporting furs and fish, which, in turn,

required preservation of the existing forests. Thus, their early

longarms were usually lighter, of smaller bore and better balanced

for traveling in rough terrain. Captured examples were, in fact,

preferred by a number of Britain’s new light infantry companies

learning to fight in thick woodlands during the French and Indian

War. Group II: The Regular

French Army in North America At the outbreak of the

French and Indian War, France sent regular army regiments (troupes

de terre) to defend New France beginning in 1755. They brought the

heavier, standard muskets designed for open-field fighting in

Europe. Most were produced under the supervision of artillery

officers at the three royal manufactories: Charleville, St. Etienne

and Maubeuge. Tulle became the fourth in 1777—primarily for naval

arms. This period is best typified by two patterns, each identified

by its original date of issue: the Model 1717 and the Model

1728. Group III: France’s Aid

to the American Revolution Following the momentous

loss of New France to Britain in the French and Indian War, a new

musket design, the Model 1763, eliminated the familiar Roman-nose

profile and established a basic form that would endure through the

Napoleonic years. Charleville

Fore-Ends/Muzzles

|

|

Evolution of the French Longarms (1730-1783) Arms from the author’s collection. Photos by Lance Rickenberg of J.C. Devine, Inc. | |||||

|

| ||||

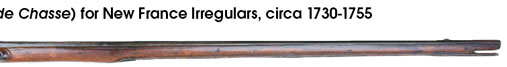

| These light, well-balanced firearms intended for wilderness use were favorites of New France’s woodsmen, militia and their Indian allies. The long, slender walnut stock had a Roman-nose butt and extended to the muzzle. Its flat/beveled lock, in turn, mounted a swansneck cock and a faceted pan, but lacked an exterior bridle. Raised stock carving surrounded the barrel tang, sideplate and lock. The French naval ministry controlled New France and contracted for most of these arms from the independent manufacturer at Tulle, plus some from St. Etienne. Tulle-style iron furniture included a flat, “L” sideplate with an oval center, a double-pointed trigger guard and a butt tang ending in a pear-shaped finial. This example has a 44 1/2", .62-cal., smoothbore pinned barrel, a wooden ramrod and no sling swivels. | |||||

| Length: 60

3/4"

Barrel: 44 1/2", .62 cal. |

Lock: 5 3/4"x1" Trigger Guard: 11 1/2" |

Butt Tang: 3 1/4" Sideplate: 3 1/2" |

Furniture: Iron Weight: 6.8 lbs. | ||

|

| |||||

|

| ||||

| The professional infantry defending New France prior to the French & Indian War were the naval ministry’s Compagnies Franches. Their muskets, fusils ordinaire, came mostly from Tulle, plus St. Etienne. They resembled the Tulle hunting gun with a Roman-nose butt, similar iron furniture, a flat/beveled lock, a wooden rammer and a smoothbore, Tulle-type pinned octagonal/round barrel. The stock, however, was cut for a socket bayonet (top stud), while the barrel was lengthened to 46 3/4" with a larger .66-cal. bore and an exterior bridle installed. A revised version for grenadiers (shown here) added a center band holding an inboard, round sling swivel (the second ring was behind the lower lock screw) and shortened the barrel to 44 3/4". Many of the St. Etienne arms followed Tulle’s configuration, but substituted the French army’s Model 1728 sideplate, trigger guard and buttplate designs. Weight averaged 7 to 8 lbs., and all raised stock border carving was gone. | |||||

| Length: 59 3/4"

Barrel: 44 1/2", .66 cal. |

Lock: 6 1/2"x1 1/4" Trigger Guard: 11 1/2" |

Butt Tang: 4 3/4" Sideplate: 4" |

Furniture: Iron Weight: 7.8 lbs. | ||

|

| |||||

|

|||||

| France was the first country in Europe to establish a standard army musket with its Model 1717. It had a pinned, 46 3/4"-long, .69-cal. barrel, plus a single center band mounting a round, inboard sling swivel (the other ring was below the lock’s lower side screw). An exclusive, vertical outside bridle joined the frizzen and frizzen spring screws. The flat/beveled lock also included a swansneck cock having a flat-backed top jaw and a frizzen spring ending short of the side screw tip. Its walnut stock displayed a Roman nose with a round wrist and an absence of raised stock borders, while the round barrel showed an octagonal breech that continued a flat top panel to the bayonet lug. Its iron furniture contributed a long worm-like pinned butt tang, a flat “L” sideplate, a double-pointed trigger guard (with two screws) and four 1 1/8" iron pipes for a wooden ramrod. Normal weight was 8 to 9 lbs. Production totaled 48,000. This example’s “crown/SE” mark identifies St. Etienne. | |||||

| Length: 63 1/4"

Barrel: 47", .72 cal. |

Lock: 6 1/2"x1 1/4" Trigger Guard: 11 1/2" |

Butt Tang: 4 3/4" Sideplate: 3 7/8" |

Furniture: Iron | ||

|

| |||||

|

|||||

| This important workhorse musket introduced a new horizontal exterior bridle and replaced the prior barrel pins with three iron bands, of which the center one held a side sling swivel. A rear spring secured the top band; the other two were held by friction. Additional changes included a longer frizzen spring on the flat/beveled lock to cover the forward side screw tip and a cock’s post that was rectangular with a wrap-around oval upper jaw. Its barrel remained 46 3/4" long and in .69 caliber, keeping the previous octagonal breech and flat, top panel. The iron furniture continued the long, narrow butt tang, flat “L” sideplate, double-pointed trigger guard, and round inboard sling swivels. It had a walnut stock with a Roman-nose butt and sloping comb that omitted both an escutcheon and raised carving in the French military tradition. A steel rammer replaced the wooden rod beginning in 1741. Production reached 375,000 muskets, and the “SE” lock stamp identifies this example’s origin as a St. Etienne. | |||||

| Length: 62"

Barrel: 45 7/8", .72 cal. |

Lock: 6 1/2"x1 1/4" Trigger Guard: 11 3/4" |

Butt Tang: 4 3/4" Sideplate: 4 1/8" |

Furniture: Iron Weight: 8.2 lbs. | ||

|

| |||||

|

| ||||

| The 1763 Model was part of a reorganization of France’s armed forces after the French and Indian War. Its basic, new, three-banded pattern had a straightened butt profile that continued through the Napoleonic years. Moreover, the barrel was shortened to 44 3/4", though it was still in .69 cal., and the earlier octagonal breech became rounded with flat sides. A revised flat/beveled lock mounted a ringed cock having a notched upper post, a wrap-around oval top jaw, plus a hole in the slotted jaw screw. An exclusive feature was the long “U”-shaped iron strip riveted to the top band’s underside that extended back to cover the ramrod channel to slip under an added lip on the center band. Rear springs held the two upper bands, but not the bottom one. The iron furniture introduced a lobed butt tang (top screw) and bell-shaped sling swivels underneath, but retained the earlier “L”-shaped sideplate and pointed trigger guard. Its steel rammer now had a trumpet shape. Total weight was nearly 10 lbs., and 88,000 were made. | |||||

| Length: 61 3/8"

Barrel: 45 1/4", .78 cal. |

Lock: 7"x1 1/4" Trigger Guard: 8 7/8" |

Butt Tang: 2 1/2" Side Plate: 4" |

Furniture: Brass Weight: 9.1 lbs. | ||

|

| |||||

|

| ||||

| The Model 1763 was too heavy, and this lighter revision became the Model 1766. Its similar flat/beveled lock (with a ringed cock) was shortened by 1/2", while the walnut stock was slimmed and the Model 1763’s long, iron, ramrod cover was replaced by a pinned spring under the breech. A thinner-walled barrel kept its 44 3/4" length and .69-cal. bore. The uppermost of three barrel bands replaced the prior squared-back edge with a sloping tail, and only the bottom band still lacked a rear spring. Its steel ramrod was changed back to a button-head form. The lock face of this example is marked, “Maubeuge,” and production reached 140,000. Circa 1768-1773 many existing muskets were upgraded in France. The Model 1766 revisions added the bottom band spring and that final configuration was subsequently copied by America after the Revolution as its first official arm, the U.S. Model 1795. This example is marked on the breech as one of those delivered to New Hampshire in 1777, “NH 3B No. 288.” | |||||

| Length: 60

1/2" Barrel: 44 3/4", .72 cal. |

Lock: 6 1/4"x1 1/4" Trigger Guard: 12 3/4" |

Butt Tang: 2 1/2" Sideplate: 3 7/8" |

Furniture: Iron Weight: 8 1/2 lbs. | ||

|

| |||||

|

| ||||

| The Model 1774 was the newest of the patterns sent to the American rebels. As the 1770s progressed, the musket innovations continued. Similar shaped flat locks became rounded with rounded cocks and flashpans in 1770. In this Model 1774, the front end of its trigger guard was shortened to 2", a forward lip appeared on the center band, and the lower band showed a convex screw head that held an internal ramrod spring. Most of the iron furniture remained the same. In addition, the frizzen replaced the previous curled tip by a squared front stud. An exclusive feature was the spring catch projecting out under the muzzle to snap over the rear socket ring of a new bayonet design. The walnut stock reduced the comb height, while a steel trumpet head rammer replaced the prior button head. A total of 70,000 were manufactured. The lockplate of this example is marked under the pan by its source, “Charleville.” | |||||

| Length: 60"

Barrel: 44 3/4", .72 cal. |

Lock: 6 1/4"x1 1/4" Trigger Guard: 11 1/4" |

Butt Tang: 2 3/8" Sideplate: 3 7/8" |

Furniture: Iron Weight: 9 lbs. | ||

|

| |||||

|

| ||||

| The innovative Model 1777 continued with modifications as the French standard musket throughout the Napoleonic Wars. It was not shipped to the American rebels, but did arm General Rochambeau’s regiments leaving for America in 1780 and others that served on our soil. The new pattern retained a 44 3/4", .69-cal. round barrel but introduced several changes. They included: a slanted brass flashpan (no fence) and bridle; two, rear-finger ridges on a shortened trigger guard; a cheekrest cut into the buttstock’s inboard side; a forward spring for the lower barrel band; a bend at the top of the frizzen; and a radical, locking center-ring bayonet. Collectors often incorrectly date this arm by the barrel tang marking, “M.1777,” which was continued into the 1800s. To identify the first version, which was used here in the Revolution, look for a screw head on a raised collar at the lower outboard side of the top barrel band. That early form lacked a middle band retaining spring. This example’s lock is marked “St. Etienne.” | |||||

| Length:

60" Barrel: 44 3/4", .73 cal. |

Lock: 6 1/4"x1 1/4" Trigger Guard: 9 7/8" |

Butt Tang: 2 1/2" Sideplate: 3 7/8" |

Furniture: Iron Weight: 8.7 lbs. | ||